Stunning images of ‘galactic fireworks’ hold the secrets of how stars form

Galaxies are unfathomably huge, dynamic beasts made up of stars that burst into and out of life in cosmic blinks of an eye.

Yet we’ve barely been able to observe the mysterious life cycles of galaxies beyond our own.

Now, spectacular images of galaxies just next door to the Milky Way, captured by an international team of astronomers, are allowing us to do exactly that.

To the trained eye, every golden spark and purple haze contained in these “galactic fireworks” pinpoint where new stars are emerging and reveal the intricate processes that shape their birth.

“We’re seeing if we can capture the life cycle of a star, just like you capture the life cycle of creatures here on Earth,” said team member Brent Groves, astronomer at the University of Western Australia.

“Each pixel contains a whole rainbow of information.”

Capturing stars being born

While astronomers know that new stars emerge from clouds of cold gas, they haven’t been able to observe this process in detail or figure out how it occurs.

The new images were taken as part of the Physics at High Angular Resolution in Nearby GalaxieS (PHANGS) survey, which observes nearby galaxies to understand the processes behind star formation.

Each image is essentially a composite of images that capture nearby galaxies in different wavelengths.

And the results are breathtaking.

The orange tones represent clouds of molecular gas, the raw material from which stars form, while the darker brown patches indicate the presence of interstellar dust.

“Like smoke from bushfires, this dust makes stars darker and redder,” Dr Groves said.

When stars are first born, they heat up the cold gas around them, creating warm clouds of charged hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen.

This process is represented by the bright spots of gold in the images.

On the other hand, the bluish tones are the signatures of stars that have already formed.

“The bluer the light, the more massive the stars that are there,” Dr Groves said.

“And because big stars burn bright and die young, it means you’re seeing regions where stars have recently formed.”

Peering into our galactic neighbours

The images also reveal how diverse these nearby galaxies are, said team member Rebecca McElroy, an astronomer at the University of Sydney.

“There’s enormous diversity. It’s overwhelming,” Dr McElroy said.

For instance, the NGC 1300 galaxy, located 65 million light years away in the Eridanus constellation, looks relatively sparse compared to the others.

This tells astronomers that there isn’t as much gas hanging around in the galaxy, with most of its stars forming along the spiral arms on the outer edges.

In contrast, the soft golden glow throughout NGC 1087, which sits 80 million light years away in Cetus, reveals that it’s rich in star-forming gas clouds.

How did they get the images?

The team combined observations taken by the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile.

With ALMA’s 66 radio telescopes, the researchers were able to map about 100,000 cold-gas regions across 90 nearby galaxies, creating a detailed atlas of nearby stellar nurseries — the birthplaces of new stars.

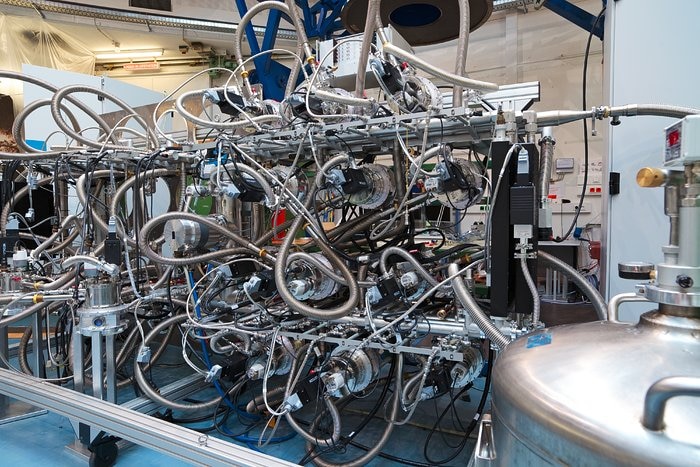

The secret to the incredible detail in the images is a bizarre looking instrument called the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE), which is attached to the VLT.

“It looks like one of the monster robots from The Matrix,” Dr McElroy said.

This instrument splits light into its component parts, just like a window that separates a beam of sunlight into a rainbow on the wall.

These “bar codes” of light, or spectra, represent different chemical elements.

“We can analyse the ‘rainbow’ and see what elements are emitted by that galaxy,” Dr McElroy said.

In this survey, MUSE observed 30,000 clouds of warm gas and collected about 15 million spectra of different galactic regions.

The next step for the team is to begin zooming in on some of the features in the images to take a closer look at what’s going on in our galactic neighbours.

In addition to peering into the star formation process, Dr Groves said that the reams of information in each image could tell astronomers about how certain elements are spread across galaxies.

“The data is just so rich,” Dr Groves said.

Dr McElroy’s eyes will be focused on the centre of these galaxies to learn more about their supermassive black holes.

“They’re all very weird and wonderful,” Dr McElroy said.

Republished from ABC Science / By science reporter Gemma Conroy